- Astronauts and space tourists face risks from radiation, which can cause illness and injure organs.

- Researchers used supercomputers to investigate the radiation exposure of an historical space mission.

- Improved computation times could one day model astronaut radiation exposure in real time.

Alongside the well-known hazards of space — freezing temperatures, crushing pressures, isolation — astronauts also face risks from radiation, which can cause illness or injure organs.

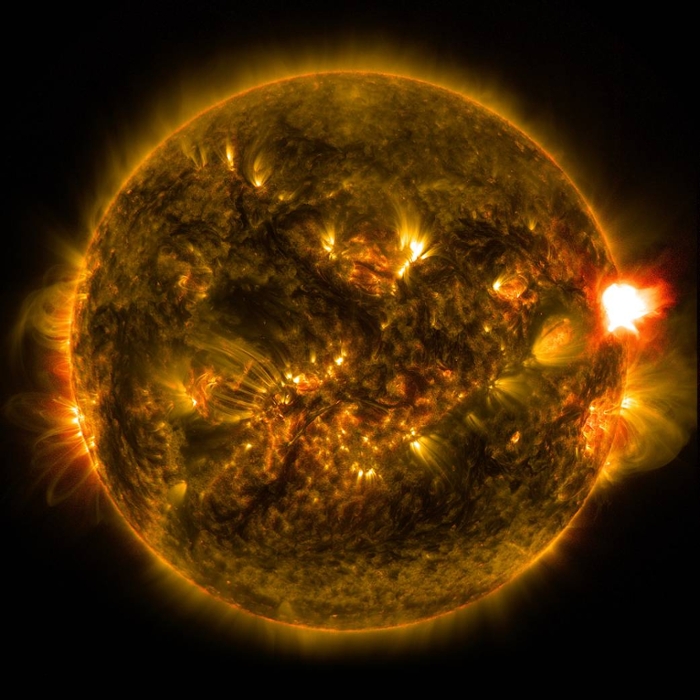

Though not believed to be an imminent threat to current missions, astronauts may one day face radiation from solar winds and galactic cosmic rays. How much radiation, what kind, and what the anticipated health impacts of this exposure would be to astronauts are open questions among space agencies.

, a research scientist at , has spent more than a decade studying these questions as part of four missions.

Recently, collaborating with physician and NASA scientist and astronaut , Chancellor .

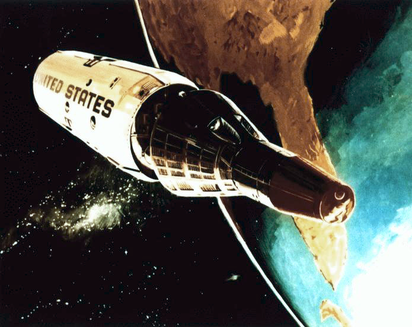

The researchers used as a test case the , which was conceived in 1963, but never actually flew.

"It was such a unique orbital profile," Chancellor says. "Polar, low altitude… I couldn't guestimate what the effects would be. So, I decided to take a step back and apply advanced computational and numerical methods to this mission profile."

They found that the relatively minimal shielding of the MOL program's space vehicle and its high inclination polar orbit would have left the crew susceptible to high exposures of cosmic radiation and solar particle events.

Eyes in the skies

The MOL was conceived as an experimental laboratory for human spaceflight, but was recast as a secret reconnaissance platform in 1965 during the height of the Cold War.

The vehicle would have travelled in low-earth orbit and passed repeatedly over the northern and southern polar regions. This type of orbit incurs greater radiation exposure than orbits closer to the equator because it is less protected by the Earth's gravitational field.

The vehicle would have travelled in low-earth orbit and passed repeatedly over the northern and southern polar regions. This type of orbit incurs greater radiation exposure than orbits closer to the equator because it is less protected by the Earth's gravitational field.

In August 1972 — three years after the MOL mission planning was discontinued — the Earth experienced a historically large solar particle event. Chancellor wondered how this radiation would have impacted MOL pilots who orbited for 30 days in the thin-shielded vessel.

The researchers focused on radiation from two sources: solar winds and galactic cosmic rays. Some space radiation is believed to pass through the walls of shuttles. A portion passes through the body; the rest deposits its energy on the skin or even inside the body, affecting the organs.

Determining the radiation levels that MOL pilots would have experienced behind the vehicle's light-weight shielding entailed data mining, extrapolation, and simulation. Chancellor and his collaborators modeled the MOL's orbit profile, the space weather, and geomagnetic forces from those years, and the particle and heavy ion transport that such a trajectory would have encountered.

Combining these factors, sampling them, and simulating them thousands of times on TACC's supercomputer, Chancellor and his collaborators found that, under normal conditions, the MOL crew would have endured 113.6 millisievert (mSv; a measure of radiation dosage) to their skin and 41.6 mSv to blood-forming organs (e.g., bone marrow or lymph nodes) during a 30-day flight — well within the exposure limits for NASA astronauts.

However, during the "worst-case scenario" of the 1972 solar storm, their skin would have been exposed to 1,770 mSv, while their organs would have experienced 451 mSv, both of which exceed NASA exposure limits.

Such exposure would have caused nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and possibly skin burns to crew.

Though the study explored the historical MOL missions, the researchers have in mind future commercial space flights, like those proposed by SpaceX or Virgin Galactic, that will likely travel a similar orbit to show off the beauty of Earth from space.

Overcoming limits

Efforts to simulate space radiation risk are not new. But decades of study have achieved few practical measures to mitigate radiation.

"Despite years of research, understanding of the space radiation environment, and ," says Chancellor.

"Despite years of research, understanding of the space radiation environment, and ," says Chancellor.

But, until recently, scientists did not have the capabilities to do radiation simulations accurately.

“This is an area where better algorithms and more powerful computers make a big difference in what's possible,” says Chancellor. “I don't think we would've made this progress without the ability to use high-performance multicore computers. It's a game-changer."

Each of the three test cases from the MOL that the team ran on Lonestar5 required 150,000 computational hours and generated 2.5 terabytes of data.

"The fact that I could parallelize the problem and have 1,000 processors running each computation and do that in three to four hours instead of three to four months is a huge benefit," he says. "The more samples you take, the more accurate the results and the more confidence you have."

When Chancellor re-ran some of his computations on , TACC's latest supercomputer and one of fastest in the world, he was able to obtain a result in five minutes as opposed to five hours.

"It's smoking fast," Chancellor says. "When I first started getting results off of Stampede, I called my friend who works in mission control for radiation at NASA and said, 'You guys have to get on this.'"

This rapid turnaround could enable NASA to run much more accurate models and determine, in real-time, how a solar storm or other cosmic event might impact astronauts — a capability that may one day save lives.